Research

Key areas of research:

- Chemotaxis

- Biofuel and bioproducts

- Methanotrops

- Microbial food

- Plastic conversion

- Computational biology

Chemotaxis

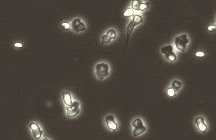

Our lab collaborated with George Ordal to investigate chemotaxis in the model Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. While Escherichia coli has long been the paradigm for bacterial chemotaxis, the pathway architecture is not conserved in other species of bacteria. Interestingly, B. subtilis behaves in an identical manner to E. coli with regards to chemotaxis. The pathways in the two bacteria also have homologous proteins. Yet, how these proteins are “wired” to one another in the two pathways is entirely different. We seek to understand why these two pathways are “wired” differently and the extent of degeneracy in the basic design.

Oleaginous yeast

We have worked with different yeasts like Yarrowia lipolytica, Rhodosporidium toruloides, and Lipomyces starkeyi , which can get “fat” by storing lipids inside the cell. We have been engineering these oleaginous yeasts for the production of valuable oleochemicals from plant-based sugars. We are also interested in understanding the mechanisms of substrate utilization and identifying key genes and metabolites within lipogenic pathways.

Methanotrophs

Methane emission into the atmosphere has negative consequences, as it is a greenhouse gas with approximately 20 times the impact of carbon dioxide. Methanotrophs use methane as their sole carbon source and convert methane into cellular components or transform it into valuable products. Biological processes utilizing these microorganisms may provide a more economical alternative to existing gas-to liquid conversion processes (e.g. Fischer-Tropsch), because they are less capital intensive, do not require extreme operating conditions, and can potentially be deployed at smaller scale to capture remote gas. Our lab is working on production of value added chemicals using methane as a substrate. Our main goal is to optimize mass transfer rate and methane uptake by methanotrophs using lab scale bioreactors to convert maximum methane into biomass and valuable products.

Microbial Food

The goal of this project is to develop an on-site food generation system using only air, water, and electricity as the inputs. To achieve this goal, we are exploring acetate as a microbial substrate production, because it can be electrochemically produced from CO2, is soluble, and readily metabolized by many microbes. We specifically seek to develop a platform whereby acetate can be fed to GRAS (generally recognized as safe) microbes to manufacture biomass with tailorable ratios of protein, carbohydrates, fat, and fiber fit for human consumption. Our main goal is to use metabolic engineering in oleaginous yeasts (Yarrowia lipolytica and Rhodosporidium toruloides) and algae (Chlorella vulgaris and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) to improve and manipulate the conversion efficiency of acetate as a carbon source to macronutrients. These hosts have unique metabolic pathways enabling them to grow on acetate and act as a cellular factory for valuable chemicals and fuels. Genetic engineering can also be used to implement pathways into model yeast strains like Bakers’ yeast for vitamin and flavor synthesis as additives for palatable food. This system is designed to create a sustainable production of food with no waste, better process efficiency, and less power usage.

Plastics conversion

One of the major issues faced by the modern world is the threat presented by plastic pollution. Only approximately 30% of all 8.5 billion tons of plastics ever produced is still in use, with the remainder ending up in landfill or the environment, being incinerated, or recycled into secondary and tertiary grade polymers. At best ,post-consumer plastic is an eyesore and uses up land that could be used for more lucrative purposes. When burned, it releases toxic volatile compounds that cause illness in humans and wildlife when inhaled. In the environment it kills thousands of wildlife when they ingest or become entangled in it, harbors flora and fauna that can float to new environments where they can become invasive, and can trap toxic compounds that can biomagnify as organisms of succeedingly higher trophic levels consume lower level organisms. Plastics are prized for their stability and durability in their respective applications; these same characteristics render them difficult to degrade under normal environmental circumstances. Coupled with their cheap and easy production capacity, and their utility in single use applications, the scale of plastic pollution has reached levels never before seen and presents a serious issue to the health of our cities and environment.

In the Rao lab, we work on techniques to engineer proteins, organisms, and microbial communities to overcome limitations in plastic degradation. We investigate the ability of organisms to sense and migrate towards plastic particles in their environment, the overproduction and secretion of plastic-degrading enzymes in close proximity to these plastics, and the improved performance of plastic-degrading enzymes to degrade plastics on effective time scales.

Computational biology

We use mathematical modeling and bioinformatics as tools to complement experimental research in our lab. Our objective is to create simple and intuitive models for biological processes that can further guide our understanding of the systems and help with experimental design. We have tools to generate and analyze different types of omics data for bacterial and yeast systems, to generate insights into cellular mechanisms. One of our newer ventures is using fluid dynamics to investigate isogenic heterogeneity arising from nutrient availability for fermentation scale-up.